An Essential Guide to Chess 960 (Freestyle Chess Format)

In a world where chess engines and artificial intelligence’s machine learning have deeply influenced the game, the growing popularity of Chess 960 aims to be a counterbalance to mechanical calculation and memorization.

What Is Chess 960 or Fischer Random Chess?

Don’t get confused—Chess 960 is also known as Fischer Chess, Fischer Random Chess, Freestyle Chess, or even 9LX Chess. It’s a relatively new format compared to classic or traditional chess.

While both games follow essentially the same rules, there’s one crucial and dramatic change in Chess 960: at the start of the game, the pieces on the first and eighth ranks are placed randomly. This forces players to think creatively from the very first move.

It’s called “Fischer Chess” or “Fischer Random Chess” because the legendary American grandmaster Robert James Fischer (1943–2008), better known as Bobby Fischer, was the one who came up with the idea. But we’ll come back to that story in a moment.

As for the name “Chess 960,” it refers to the 960 possible random starting positions for the first and eighth ranks. That’s also where the name “9LX” comes from—LX stands for 60 in Roman numerals.

These 960 possible starting positions include the traditional starting setup of regular chess, which, in fact, corresponds to position number 518.

There are just two basic rules that must be followed when generating these positions:

-

There must always be one bishop on a light square and one on a dark square.

-

One rook must be placed to the left of the king, and the other to the right—regardless of whether there are pieces in between.

Given these two restrictions, we can use combinatorics to calculate the number of possible combinations. The formulas may vary depending on the order in which the pieces are placed. Here are two such formulas:

-

Bishops (4 × 4) × Queen (6) × Knights (10) × King and Rooks (1) = 960

-

Bishops (4 × 4) × Knights (15) × Queen (4) × King and Rooks (1) = 960

As we mentioned, position 518 is the one that’s been used at least since the 20th century. The other 959 positions already have assigned numbers to make it easier to track official games.

Keep reading—it only gets more interesting from here.

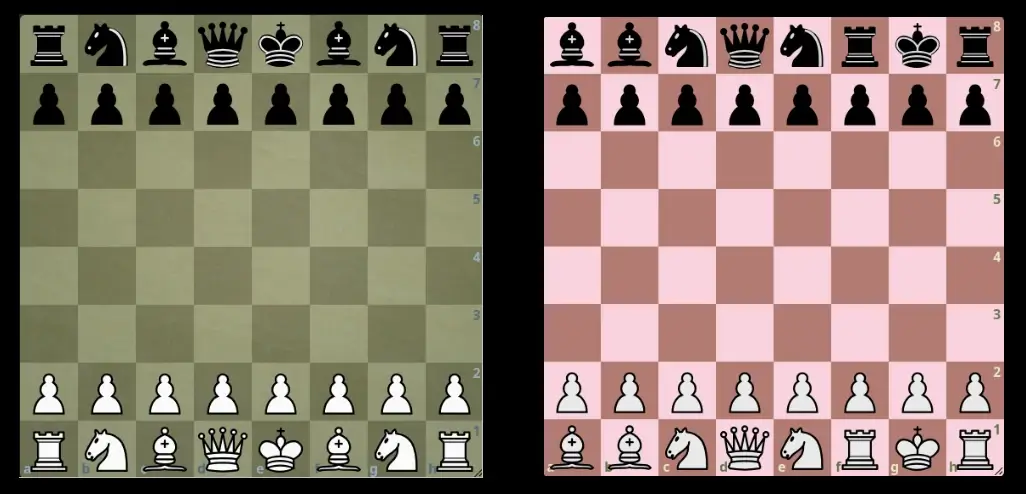

On the right, the 16th position of chess 960.

Image generated with AI

When and Why Was Fischer Random Chess Created? And Why Is It Coming Back Now?

Yes, Chess 960 was created by Bobby Fischer, but it’s important to understand the context and the reasons behind it.

That context includes the steady advancement of chess engines, the early development of artificial intelligence, and chess as a testing ground for these technologies. As a parentheses, we recommend that you also learn about the historical background of the relationship between chess and artificial intelligence .

Let’s go back to the 1980s. According to the book Bobby Fischer: The Wandering King by Hans Böhm and Kees Jongkind, Fischer was already expressing a desire for a renewal in chess during that decade. But it wasn’t until 1992 that Fischer introduced two valuable contributions to the game: the chess clock and random chess.

With Chess 960, Fischer wanted to:

-

Eliminate theoretical opening prep and memorized knowledge. In most elite GM games, true originality only begins after move 20. Openings had already been deeply analyzed and memorized—all starting from the same known position.

-

Push back against the dominance of chess engines—because the player with the more powerful computer wins, often without a real understanding of the game.

According to Böhm and Jongkind, and unlike today’s version of Chess 960, Fischer originally proposed that the game begin with White choosing a starting piece layout, and Black deciding whether to mirror it or select a different setup.

The authors also point out that Fischer wasn’t the first to want to eliminate opening prep. As far back as the early 20th century, some were advocating for it. But Fischer was the first to seriously dedicate himself to designing a new version of the game.

Fast forward 16 years after Fischer’s death, and a key moment marks the current relevance of Chess 960: the 2017 defeat of Stockfish by AlphaZero—a self-learning system powered by neural networks and general-purpose algorithms.

This new era is also being supported and promoted by none other than Magnus Carlsen, considered by many to be the greatest chess player of all time. Carlsen has distanced himself from FIDE in a kind of a similar way Fischer once did and recently co-founded the Freestyle Chess Grand Slam Tour.

In a way, the AlphaZero–Stockfish result echoes the concerns raised by Fischer and Carlsen about the over-reliance on engines and the mechanical memorization of long opening lines. AlphaZero’s win challenged the very idea of rote memorization and lack of creativity.

In Game Changer by Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan, research engineer and AlphaZero team member Matthew Lai explains:

“One interesting thing we found is that AlphaZero re-discovers opening sequences that are frequently played by human players as well. What we found most amazing is that, as training progresses, AlphaZero often discards those known variations because it finds ways to refute them!”

AlphaZero blends memory and imagination—two traits often tied to intelligence—and outperformed traditional engines like Stockfish.

“…AlphaZero is unconstrained by human design or lack of imagination and has complete flexibility in choosing the features it takes into account when evaluating a given position.” (Game Changer)

In that same book, we also learn that in his doctoral research, Demis Hassabis—central figure in developing AI and AlphaZero—discovered that the hippocampus, besides being crucial to episodic memory, is also involved in imagination (understood as mental simulation) and future planning. That is, there’s a systematic link between the reconstructive nature of memory and the constructive process of imagination.

In light of all this, is it truly necessary to shift from classical to 960?

AlphaZero’s triumph at least raises the question. Perhaps chess players, shaped by traditions that allowed engines to emerge in the first place, were too reluctant to take creative risks—and made the game more tedious in the process.

Still, maybe the only way to unlock both classical chess and the minds of its players is through the radical shift that Chess 960 offers, as we’ll see below.

How Does Chess 960 Differ from Traditional Chess?

Tournaments like the Grenke Freestyle Chess Open—part of the 2025 Freestyle Chess Grand Slam Tour—have helped showcase some of the defining traits of Chess 960. Among them:

-

At least in these early stages, there’s no set preparation. Players don’t rely on databases or memorized lines—they lean more on sharp intuition and creativity in the moment. Every move matters from second one.

-

Over-the-board skills take precedence over engine-backed prep.

-

While opening theory isn’t helpful, it does help to understand how to manage uncommon setups—bishops in the corners, oddly placed queens or knights, strange castling options, etc.

-

Unlike classical chess, where opening mistakes can be salvaged with theory, Chess 960 punishes even small errors quickly.

-

Even tactics like bishop sacrifices need to align with broader positional goals. Remember that sacrifices aren’t just flashy—if they don’t support your larger plan, they often backfire. In 960, tactical fireworks still need strategic logic.

-

Players with prior freestyle tournament experience have an edge, as they react more intuitively to unfamiliar positions.

-

In tournaments like the Grenke Open, time controls are the same as in classical formats, but freestyle games demand more focus due to the novelty of the positions.

-

From move one, the big question is: how to develop your pieces now that theory is off the table?

-

Understanding core principles like central control, development, and king safety matters more than memorizing lines.

-

It’s possible to build a winning strategy within the first two or three moves, highlighting the value of early evaluation.

-

Symmetry can be a double-edged sword. Strong players try to disrupt it early. Mirroring moves often leads to lost initiative. The one who breaks symmetry first usually gains the upper hand.

-

Players must find ways to restrict their opponent’s pieces from the outset and respond to mirrored or symmetrical strategies.

-

Super-flexible strategies are a must, specially when you are unfamiliar with the results of the opening.

-

Freestyle chess levels the playing field—a 2200-rated player could hold their own against a 2700 in the middlegame, or even pull off an upset. Still, top players’ ability to spot a plan quickly gives them a practical edge.

-

Many games revolve around how fast players can coordinate their pieces from unfamiliar starting positions.

-

Preferred moves are based more on practical judgment than engine-calculated lines.

-

Even in freestyle formats, classical positional ideas return in the endgame—meaning winning positions still require accurate conversion.

-

Fatigue or miscalculations are more frequent due to the lack of theoretical scaffolding.

-

Looking dominant on the board isn’t enough unless moves are precise. As in classic chess, human intuition can diverge from computer evaluations.

-

Evaluation swings of +2 or more can come from just one small mistake, showing how volatile freestyle positions are.

-

Good sleep, rest, a clear mind, and flexibility are more valuable than memorization.

-

It’s recommended to take a light walk before the game to keep the brain alert, and to warm up with tactical exercises.

Let’s not end without saying that don’t forget to try a game of Chess 960 and see how it changes your thinking.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article—or at the very least, found it interesting!