Judit Polgar: A Must-Know Story for Every Chess Player

Few personal stories serve as a beautiful synthesis or perfect intersection of other stories, processes, or important topics. That is the case of the chess career of the great Judit Polgar.

“#CSW61 – Side Event - “Fighting Stereotypes with Judit Polgár, Chess Grandmaster and Planet 50-50 Champion”” by UN Women, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Why Is It Important to Know Judit Polgar’s Career?

Anyone initiated into chess, whether woman or man, should read about the life and achievements of Judit Polgar. In fact, anyone would benefit from knowing her story.

Talking about the career of the Hungarian Judit Polgar in chess means entering the realm of three essential topics:

-

The pedagogy of childhood not only to train chess players, but to aid in the development of transferable skills to other areas of human life.

-

Discrimination in chess for being a woman, or whether women’s chess can compete at the same level as men’s.

-

The differences in cognitive learning after the emergence of AI in chess.

Thus, speaking about Judit Polgar is an invitation to talk about the Polgar family, the importance of early-age pedagogical models, the era and characters who shaped chess before the arrival of AI, and the alternate stories that intersect on her path to success.

Judit Polgar’s Achievements

If Judit’s story were not one of success and deep meaning, we wouldn’t be writing this now.

It is enough to look at her achievements to understand why her story borders on the legendary and the epic.

One of the most outstanding feats is having defeated top-ranked players in the world, including several male world champions.

These are the 11 world champions defeated by the one justifiably considered the greatest female chess player in history and one of the legends of world chess:

1. In New Delhi, 1990, Judit Polgar defeated Viswanathan Anand, a future world champion, with the white pieces. In 1991, she beat Anand again in Munich, also with white.

She would defeat Vishy once more in the 1999 Dos Hermanas tournament with white.

In 2003, they faced off in a seven-game rapid match at the Mainz Festival: Judit won 3 games, Vishy won 4.

Later that year, in the 2003 Rapid World Championship in Cap D’Agde, France, Judit won again, this time with black.

2. In 1993, at the end of January, at the Intercontinental Hotel in Budapest, Hungary, Judit played a ten-game match against Boris Spassky. The final score: 3 wins for Judit, 5 draws, and 2 wins for Spassky.

In the 1994 Monte Carlo Dos Hermanas tournament (Women vs Veterans), she defeated Spassky again, this time with black.

The women’s team consisted of: Hungarian sisters Susan and Judit Polgar, Georgians Maia Chiburdanidze and Nana Ioseliani, Georgian-Scot Ketevan Arakhamia, and Chinese player Xie Jun. The veterans were Smyslov, Spassky, Portisch, Larsen, Ivkov, and Hort.

3. In 1993, in the Dos Hermanas tournament in Seville, Spain, she beat Alexander Khalifman with black.

4. She defeated Vassily Smyslov with white in Monte Carlo (1994) in a women vs veterans event. Though Smyslov was 63, he had been a Candidates finalist at that age.

Two years earlier, in 1992, at another women vs veterans tournament on Aruba Island, Smyslov called Judit “Tal in a skirt,” referencing Mikhail Tal, the former world champion known for his creative and sacrificial play.

4. In 1996, she defeated Anatoly Karpov in Monaco playing with white.

6. She beat Garry Kasparov in rapid at the Russia vs The World match held in Moscow in 2002.

7. In 2002, in Benidorm, Spain, she beat Ukrainian ex-world champion Ruslan Ponomariov in a rapid game with black.

8. During the World Championship in San Luis, Argentina, 2005, she beat Rustam Kasimdzhanov with white.

9. In 2006, in Hoogeveen, Netherlands, she defeated Veselin Topalov twice—once with white and once with black.

10. At the Blitz World Championship in Moscow, Russia, in 2009, she defeated Vladimir Kramnik with white.

11. She first defeated Magnus Carlsen in a blitz match in 2012, in Mexico City, at a tournament organized by the National Autonomous University of Mexico. The match ended 3–1 in Carlsen’s favor.

She beat Carlsen again in 2022, at El Retiro Park in Madrid, Spain, in a blitz game with white.

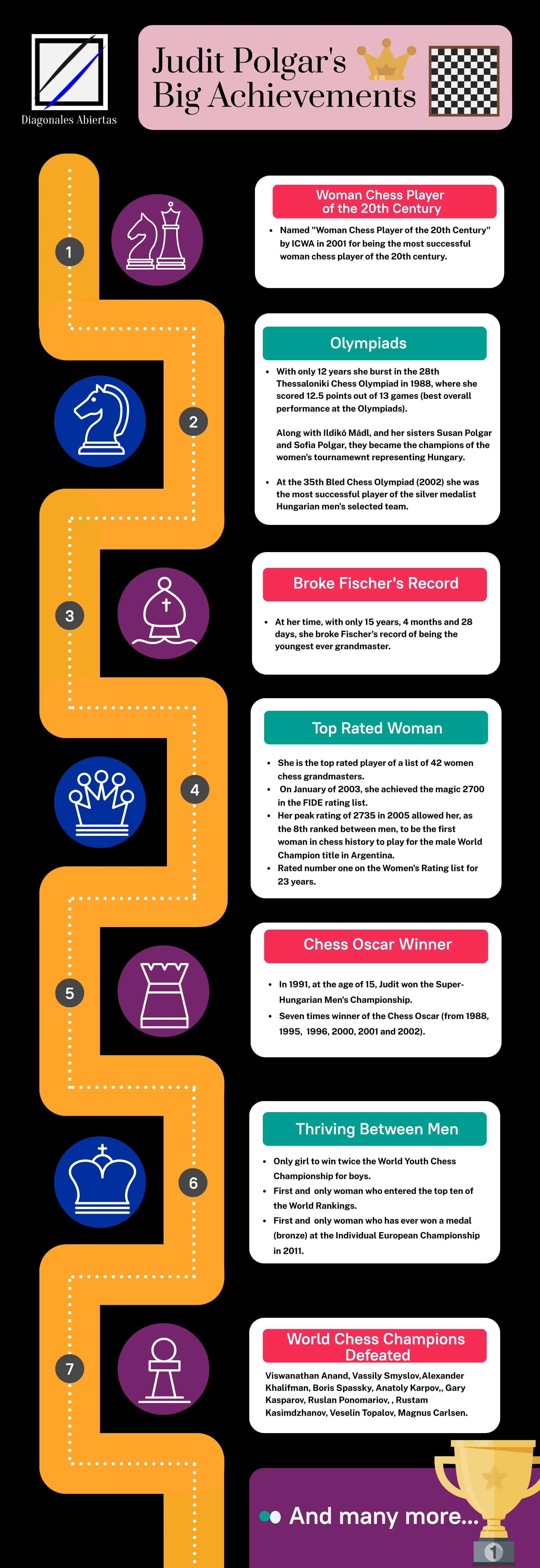

Judit Polgar Infographic

Other outstanding achievements of Judit are presented in the following infographic:

The Polgar Family’s Educational Project

In the last century, during the 1970s in Hungary, an educational project began that faced criticism and had to overcome, first, local authority obstacles and then those of the Hungarian Chess Federation.

It was an ambitious family project with a clear objective: for the three daughters not only to become outstanding individuals or geniuses, but also morally upstanding people.

The term “experiment” has been used to refer to this case, which risks adding a pejorative tone.

In reality, the more suitable term is “project” or “plan,” since it wasn’t only about maximizing intellectual capacity but also about shaping personality, based on detailed analysis of the determinants of character.

A human being should not be viewed as an experiment but as a project. In this case, it was a family project—of life, values, and beliefs.

It involved the dedication of the family members. There was a plan, a strategy, and a shared goal.

Aware that the education system rarely offers the incentives or conditions for children and youth to fully develop their abilities, the couple Laszlo and Clara Polgar devoted themselves to educating their three daughters: Susan, Sofia, and Judit.

Laszlo had degrees in philosophy and psycho-pedagogy, and his doctoral thesis focused on the development of abilities. Clara studied eight languages: Hungarian, English, Russian, German, Ukrainian, Spanish, and Esperanto.

For those interested, part of the educational philosophy proposed by Laszlo is described in his book Raise a Genius!.

The Polgár girls: Judit, Zsuzsa, Zsófia and their father, László Polgár. Author: Fortepan adományozó URBÁN TAMÁS, CC BY-SA 3.0.

What Were the Daily Routines of the Polgar Girls?

The three sisters began their education between the ages of 4 and 5.

Laszlo himself states, based on research, that the period between ages 3 and 6 is one of the most important in a person’s development. This includes not only intellectual growth, but also behavioral and personality development.

In Raise a Genius!, Laszlo suggests the following schedule for schools focused on developing geniuses, which includes 9 hours of intensive training distributed as follows:

-

4 hours dedicated to studying the child’s area of specialization

-

1 hour studying a language other than their native language

-

1 hour studying other curricular subjects

-

1 hour studying computing

-

1 hour for pedagogical, psychological, moral studies**, and development of humor

-

1 hour of physical exercise

In the case of the Polgar sisters, it’s known that Susan, the eldest, was at an age where she could receive instruction and chose chess over mathematics.

From that point on, the Polgar team was formed, carrying out Laszlo’s vision—a project where chess once again became the preferred field of experimentation.

Let’s remember that chess has also served as a testing ground and tool for artificial intelligence .

From the age of 4 or 5, the sisters spent 5 to 6 hours daily learning and playing chess. By age 5, they were already studying Russian and learning English as well.

In an interview with C-Squared , Judit mentioned that at age 9, her daily routine included waking up to play table tennis, followed by 3 to 4 hours of chess training, a break for lunch, then more chess practice in the afternoon and another 3-hour session in the evening.

Interestingly, from the time Judit was 6 until she was 11, the walls and tables in the Polgar household were lined with chessboards set up with positions to solve. This created a fully immersive chess environment, which significantly boosted her tactical abilities over the board.

12 Key Tips from Laszlo Polgar for Child Education

Anyone looking to implement an educational program for children similar to that of the Polgar family should take into account several essential tips that Laszlo shares throughout his book, including:

1. Seek the child’s active participation; do not impose anything by force.

2. Make sure the child enjoys what they do and that the activity is meaningful.

3. Set realistic goals based on the child’s current level.

4. Help the child understand the purpose of what they are doing—give them perspective.

5. Remember that the goal of intensive education is to ensure the child’s happiness through their moral and intellectual development.

6. Encourage a love of learning.

7. Trust your children, show admiration, and praise their achievements. That builds confidence. No achievement is too small.

8. Foster a positive human existence in your child.

9. Intensive education must go hand-in-hand with personality development and the formation of moral and emotional values.

10. Help your children find peers who match their intellectual level.

11. Mental state and sense of humor are crucial.

12. A loving family relationship is essential; parents must be aligned in their goals as a couple.

“Simultaneous chess exhibit v. Judit Polgár, 1992 - 22” by

Ed Yourdon, licensed under

CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The Polgar Sisters Prove That Chess Is Not a Matter of Gender

The three daughters of Laszlo and Clara became chess players of the highest level. Had they been boys instead of girls, the parents would have continued with their project just the same.

That was Laszlo’s great merit: he always believed his educational model could apply equally to both boys and girls. In doing so, he affirmed the equal intellectual capacity of all individuals, regardless of gender.

If we must look for reasons why more women aren’t competing at the same level as many men, we should consider other factors—such as early childhood education at home, the formal education system, social structures, historical gender roles, etc.

Some people have tried to discredit Judit Polgar’s achievements by saying she has a photographic memory. But it is a mistake to think that this memory was an innate gift.

Photographic memory—or eidetic memory—is a form of long-term memory involving the recall of visual information with a high degree of precision.

Many believe that the term “photographic” implies completely accurate, error-free recall. But that’s not the case. And the rarest cases of such memory are usually found in individuals with autism.

What’s called photographic memory is actually a skill that can be developed, and that there are chess mnemonics that could help.

In a 2017 study by Alixandra Barasch, Kristin Diehl, Jackie Silverman, and Gal Zauberman , researchers found that people who freely take photographs are more likely to retain visual information (but less auditory information) compared to those who don’t take photos.

If we focus and take mental snapshots—for example, of positions on the board—our retention improves. That’s precisely what young Judit Polgar was doing when she solved chess positions posted all over her home.

However, we shouldn’t assume that just teaching a child something will automatically lead to success.

In the excellent book Chess Bitch by Grandmaster Jennifer Shahade, which we highly recommend, we’re told the story of Baraka Shabazz, the first African-American woman to represent the United States internationally.

In 1981, Baraka Shabazz and Susan Polgar competed in the Under-16 World Championship in England. Susan won the gold medal, while this would be Baraka’s final international tournament.

Baraka’s father also had her study chess from seven in the morning until nightfall. But the pressure he placed on her may have been excessive—he even believed his daughter’s success would make the whole family rich.

Judit Polgar: the queen of chess

Judit was not the first to compete against men in chess, nor the first to beat a world champion, nor the first woman to become a grandmaster in chess.

For that, we have other names like Nona Gaprindashvili, Susan Polgar, or Vera Menchik, each of whom would be well worth individual posts.

But Judit has been the one who has come closest — and in the most consistent way — to that male-dominated elite of chess.

In a sport where Elo is the best way to assess a chess player’s performance, Judit broke that 2700 barrier, which no other woman has been able to achieve.

And the way several male grandmasters talk about her is always with great respect and even admiration — among them, Fabiano Caruana, Vladimir Kramnik, and Vishy Anand.

Judit Polgar’s Era: Between Human Learning and Artificial Intelligence

The relationship between chess, the human mind, and artificial intelligence is one defined by the limits of cognition and the potential of the human brain.

Judit Polgar lived through the transition from an era of human dominance in chess to one of complete dominance by computer programs supported by AI.

She shared this era with key figures such as Garry Kasparov and Vladimir Kramnik—among the last humans to seriously contend against chess engines—as well as with Demis Hassabis, whom she surpassed in Elo rating at the age of 13.

Demis Hassabis, a pioneer in AI research, studied neuroscience before launching DeepMind. His academic work explored the links between episodic memory, imagination, and future planning.

Hassabis believed that memory and imagination were the two essential components of intelligence, and that they must be integrated into intelligent systems.

Eventually, DeepMind would go on to create AlphaGo, a self-learning system that became one of the great technological milestones of our time.

In this context, Judit Polgar’s experience becomes even more fascinating.

Her chess education was profoundly shaped by the pedagogy developed by her father, which made her approach truly original.

The strength of the player nicknamed “Tal in a skirt” lay in a thought process focused on discovering combinations, rooted in creativity and problem-solving, particularly in the middlegame following the opening phase.

Let us recall that Bobby Fischer, who was once a guest at the Polgar household, complained that opening theory was ruining chess. In response, he proposed Chess960—also known as Fischer Random Chess.

Fischer’s complaint was really a critique of our cognitive approach to learning and playing chess: a criticism of how we come to understand a specific situation—such as a board position.

Many top-level chess players had forgotten the importance of basic comprehension and had shifted entirely toward memorizing opening lines. They began with theory and turned it into fixed structures in their brains—doctrine, even.

This was not only problematic for the game itself but also for the development of early chess engines.

To solve board positions, early engines relied on human-coded rules and heuristics developed over years of expertise.

But guess what? If our way of solving chess problems was limited, then those early engines were bound by the same limits.

It wasn’t until the arrival of systems like AlphaZero, which learn entirely on their own, that chess knowledge was truly unlocked—and now grandmasters are being forced to relearn the game, rediscover their imagination, and find the true spirit of play.

It’s clear that a machine’s learning method differs from that of a human. Human learning requires much more complex conditions, some of which we’ve only briefly mentioned in this article.

Judit Polgar has been openly critical of overreliance on chess engines. She preferred studying over the board and relying on intuition, while today’s players often depend heavily on engine analysis.

Judit understands the new reality—but it raises a dilemma: should a player sacrifice their own decision-making for the judgment of a machine?

How can a player improve their ability to interpret engine evaluations? Can a human’s intuition still play a vital role?

In a world where elite players and chess learners alike rely on computers to raise their level, the Polgar family’s project stands as an essential reference for anyone who wishes to follow a more grounded, thoughtful path.

Recommendations for learning more about Judit Polgar

In addition to the references already mentioned, we have drawn on various other sources, which we recommend and list below:

-

Judit Polgar, How I Beat Fischer’s Record (2012).

-

Judit Polgar, From GM to Top Ten (2013).

-

Judit Polgar, A Game of Queens (2014).

-

Matthew Sadler y Natasha Regan, Game Changer (2019).

We also recommend the following interviews:

-

Entrevista con Surya Sekhar Ganguly, In Conversation with - Episode 19: Judit Polgar - The Lioness

-

Documental de The Fifth State, Recipe for genius: How child chess prodigies master the game

-

La entrevista para Perpetual Chess Podcast, Interview with GM Judit Polgar – from the Perpetual Chess Podcast

-

La entrevista para FIDE Chess, Judit Polgar: Suddenly, it was clear it is possible for a woman to beat the world champion

-

La entrevista para ChessBase India, Greatest advice on how to raise daughters by Judit Polgar | Women Empowerment